Ten feet separated the canyon wall from the railing. Ten feet. But a busload of Chinese tourists crowded the asphalt. A surge of electric panic chilled me. My shoulders shook. My heart thudded. A deep unease roiled in my gut. Every time someone touched me I jumped. A ripe odor worse than a rancid cheese concentrated in my armpits. My fingertips led the rest of my body in a terrified creep along the cliff. A pair of tourists walked towards me along the wall. Unable to speak to them directly, I waved my hands frantically. They saw my terror and conscientiously gave me space.

I edged towards the rail, remembering a trick that I had learned from a photographer buddy who was also scared of the mere proximity of a sheer drop. The camera went to my eyes and I looked at the world through it. Everything was contained and manageable as long as no one bumped me. But they did. I snapped off a few quick shots and scurried back to the wall. The other travelers paid me no heed as they surveyed the wonders of Bryce Canyon from the head of the Navajo Loop Trail. The Bryce Amphitheater yawned as I scrambled back to what my mind told me was the more solid — and protected — ground of Sunset Point.

When I analyzed my fears with my therapist afterwards, I realized that I had been tired. I had driven — with only a stop at Fossil Butte National Monument — all the way from Jackson, Wyoming to Cedar City, Utah. Rest and a shorter hike at the Kolob Canyons section of Zion was a better plan for the day, but we were on a whirlwind road trip that took us to five national parks, three national monuments, and a national historic site in under two weeks. My eyes wanted rest. My body slouched in the driver’s seat. I panicked when I thought that I had missed a turn which proved to be farther from an intersection than I had thought. I screamed at Lynn. I drove slowly down the winding road leading to Cedar City, annoying more than one driver. The possibility of going over the side was always in my mind.

I can’t say that fear of heights or acrophobia is consistent. Standing on the edge of a cliff can make me fall to my hands and knees as I seek to feel the safety of the earth. Riding in a ski lift chair is a yawn. I can look down through the gap between my feet and worry only about dropping my camera or my lens cap. Airplanes do little to my mood — except for a little nervousness on take-off and landing. Stairs give me no problem as long as someone doesn’t stop in front of me. The key is that I keep moving. When they stop ferris wheels at their apex, I don’t like it. Ladders give me pause.

No traumatic experience precipitated me into these anxieties, no operatic scene out of Tosca marked me. I was never dangled by my heels over a chasm. I never saw a friend fall off a steep building as in Vertigo. (Vertigo, incidentally, is an inner ear problem, not acrophobia.) They’ve been there as long as I remember. And I have been mocked for their intensity.

Psychologists teach that fear of heights is not learned like some other phobias, but innate. Feet are damned unsteady things. You balance on them easily, but the complex of senses that you depend on to walk, run, and stand don’t trust them completely. The aim of these senses is to protect the head. Place the feet near any potential for a sudden drop and proprioception — the sense that lets you know where your body parts are at any given instant and where they are going — joins with other internal mechanisms to warn you of the danger posed by sheer cliffs and steep ridges. It gets worse when you are tired because the body knows that it is more inclined to make mistakes. Hence my hyper-vigilance after my fourteen hours of driving the day before and a hike at Cedar Breaks that morning.

We all start life with a healthy fear of heights. Along the way many of us lose some or most of our dread. Some of us develop a phobia or irrational fear that stops us from even the most ordinary activity. Others lose all inhibition around places threatening sharp plummets. Every now and then I read of a mountain climber or hiker who did not have any increment of my fear. The price was a life or a limb. When I read accounts of mishaps during wilderness adventures, I ask myself if I want to do anything about containing my phobia.

Therapists favor behavioral modification when helping those who want to overcome their acrophobia. Graded exposure involves engaging in increasingly challenging scenarios which trigger the phobia. A British organization devoted to helping people with phobias explains it like this:

Our session takes place on a high ropes course where the different obstacles are arranged in increasing degrees of difficulty. For example, you might start by taking a few steps on a ladder and then, once you feel comfortable at that height, move on to a cargo net. You slowly build up confidence as you choose to go to the next level.

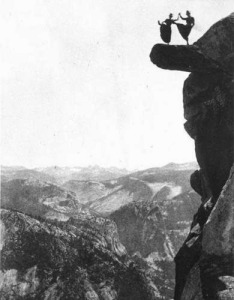

Some people treat themselves using an approach called “flooding”. This means that you just do what you fear most. Jump out of a plane. Walk the infamous El Chorro path in Andalusia, Spain. Walk out to Angel’s Landing in Zion National Park. Climb Jacob’s Ladder up the backside of Yosemite’s Half Dome.

To all these challenges I say “No thank you.” Not only are they likely to inspire me with a heart attack, but studies show that flooding doesn’t work. You jump out of the plane and land safely. You make it to the end of the path, the rim of the canyon, the top of the peak and come back intact. And you still suffer from acrophobia.

When I choose to face my fear, I do the following: First, I ensure that I am well-rested. This protects me from the most absurd episodes such as my experience at Bryce Canyon. Second, I watch what is directly in front of me or I use the camera trick to allow myself to step a little closer, minding, of course, where I am standing. Finally, I trust my instincts. Wariness around high places is an evolutionary advantage that kept our ancestors alive. Carefully evaluating situations and going slowly aid in getting past the tough spots. I don’t go for extreme experiences because people who do sometimes end up extremely dead. Still, I know that there have been times when I have been too cautious and denied myself pleasurable experiences such as when I ended my climb to a relatively low scenic viewpoint in the Grand Tetons because the path was too narrow and too crowded for my taste. Plenty of people showed me that it was safe, but the cold, nasty sweat drowned me in a blockage prevented me from negotiating through the bottleneck. I became a J. Alfred Prufrock of the back country, too scared to move on and embarrassed about the snickers from the eternal tourists who witnessed my stress. “In short, I was afraid.”