The most tiring piece of advice that you can receive when you live with depression is “Get some exercise!” There’s merit in the suggestion, but the nature of the condition is such that getting out of your bed and onto your feet can be difficult. The accusation that melancholy is due to laziness wraps its sufferers in a ball of stigma that takes some effort to escape. Buying into the belief that your sickness is due to your stubborn unwillingness to do anything traps you in a downward spiral of self doubt and anxiety.

The advice is overstated. Research shows that exercise has a moderate effect on depression. You’re not inflicting your depression on yourself by not exercising, it seems, but the lack of desire to exercise is one of its symptoms.

Those who want to help us who live with depression or bipolar disorder need to understand that we cannot just throw aside the crutches of our coping with the illness and start to walk again. I would urge helpers and caretakers to review this helpful publication from the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance before proceeding with this blog post. Sufferers stay with me. I have secrets to impart.

Physical activity when depression binds you hurts. It’s not imaginary pain: it is a physical issue in your brain. You have a real illness with real effects on your sense of well being. Psychiatrists and the popular media often characterize depression as the result of a chemical imbalance. That’s sort of true, but also untrue.

The basic model of depression has remained unchanged since the 1960s when Joseph Schildkraut, Seymour Kety, and Arvid Carlsson developed what is called the biogenic amine hypothesis” of mood disorders. These researchers and most psychiatrists today (despite what anti-psychiatrists claim) believe that chemicals and genetics contribute to only part of depression. All kinds of physiological, psychological, and environmental factors affect our state of mind. Medication offers part of the formula for successfully treating depression. Or as I like to say, they put down the floor, but you still have to build the house.

The dominance of what one critical psychiatrist calls a bumper-sticker approach to patient education — the contention that if you just get on the right kind of medication you will beat depression — has more to do with marketing by pharmaceutical companies than psychiatrists. Still many psychiatrists repeat the slogan to offer patients a quick explanation that is easy for their slowed minds to grasp. Medications have helped me. When I tell people that my psychiatrist supports my regime which includes watching what I eat, focusing on my thoughts and expectations, and hiking for ten to twelve hours each week, the ignorant are surprised but these things are central to depression treatment today.

As I said at the outset, exercise is good for depression but when you are depressed you don’t feel like doing it. The meds can make it easier to get out of your bed, but you still have more to do.

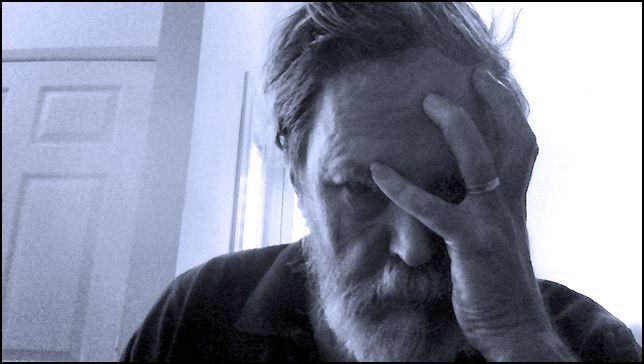

Melancholy makes exercise painful in a way that people who have broken a leg or chipped a tooth or cut a finger might not understand. As the world loses color, so does the joy you get from being outdoors doing things. In my worst depressive episode, I lay on my bed for at least eleven days. The cats joined me, sometimes sitting on top of me. From time to time I would struggle to stand and walk upstairs to change a CD. Then I would return to the mattress and while away several more hours in a waking paralysis. Toward the end, I managed to dress and put my shoes on. I counted it a triumph when I walked around the block but I always went right back to bed when I came home.

My psychiatrist increased my dose of an anti-depressant and put me on an anti-psychotic to face down suicidal ideation. I credit these with helping me reach a point where my will could overcome my resistance to physical activity.

The lifelessness affected my mind and my body. I craved the pleasures one gets from eating one’s favorite food, listening to one’s favorite music, etc. but I did not experience them. If asked to color the sensations in my limbs, I would choose gray. A long argument between what I knew what was good for me and what my being felt like doing culminated, at long last, in the resolve to hike. When I started hiking, every muscle in my body resisted movement. I would drive to my favorite trailhead, park the truck, and then spend several minutes just persuading myself to get out of the truck. The first fifteen minutes of my trek were invariably hard. The toes of my feet seemed to want to point backwards and launch into a run back to the car except that even the blessing of a downhill portends struggle and tediousness. I kept on, at first alone and later in the company of my Boston Terrier. The important thing — once I could manage it — was to keep putting one foot in front of the other again and again until I reached my destination. I was not blocked by shrieking agony but by a torment as intensely gray as my mood. My walks were very brief at first — largely out of fear that I would collapse and have to be found by some other wayfarer — but I added to them trip by trip. I went as far as I thought I was able, turned back, and realized the next time I could have gone farther. So I did until the atrophy subsided.

I am still looking for my limits.

Hiking helps my depression in several ways. First, it stirs up my metabolism, puts life into my extremities. Second, it takes me out of the four walls of my condo. It gives me escape. Seeing the same things every day for the same number of hours exhausts the spirit. The choice to walk gave my brain variety. I see different things every time I go out on the trail. I meet people — sometimes new people, sometimes regulars who share my love of places. Third, it opens the door for creativity, in my case, photography. Fourth, it grants me time to reflect on what is happening in my life when I will not be disturbed by phone calls, knocks at the door, or upsetting emails. And finally, it lets me not think about these things but about the rocks on the trail, the flowers blooming beside the path, or the clouds floating overhead.

I did not come by these things easily. I did not change my mind one day and start exercising. The will needed support from medication, meditation, and cognitive behavioral therapy. What was important when I did was that I chose an activity which I enjoyed. The chance to gain summits and take in vistas enthralled me more than doing laps in a pool or counting steps on a treadmill. Nagging never moved me to do this: My mother tried. I didn’t budge and felt the worse for it. Sometimes my wife invited me for a walk but she never forced me. I did many other things including take my meds, eat right, journal, and discuss my conflicts with a therapist. In the end, the options that were muted by the illness grew vivid once more and I was able to choose to thrive.

Thanks for sharing this.

As a fellow sufferer, I’ve had to explain: It’s not the sensation of wanting to do something and not mustering up the will. It’s the lack of desire of doing anything at all. Even doing nothing is something, so it all sucks.

I once sat on a balcony in Hawaii in utter despair. Here I was, finally visiting Hawaii for the first time, but I was deep into the grey fog. Major life changes, coupled with short stint with meds has brought me a long way.

Hiking is my therapy.

Again, thanks for sharing,

D.